What Is Maximal Extractable Value (MEV)?

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) refers to the maximum amount of value a blockchain miner or validator can make by including, excluding, or changing the order of transactions during the block production process.

The blockchain economy has experienced a period of exponential growth in the last few years, with the value locked in the DeFi ecosystem reaching $300B at its peak in 2022. However, with the growing adoption of smart contracts come new loopholes through which value can be siphoned away from unwitting users. One such example is maximal extractable value (MEV).

In this article, we’ll explore why MEV exists, examples of MEV today, and how Chainlink Fair Sequencing Services presents a novel solution to this ongoing issue in blockchain economies.

What Is MEV?

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) refers to the maximum amount of value a blockchain miner or validator can make by including, excluding, or changing the order of transactions during the block production process.

MEV occurs when the block producers in a blockchain (e.g. miners, validators) are able to extract value by arbitrarily reordering, including, or excluding transactions within a block, often to the harm of users. Simply put, block producers can determine the order in which transactions are processed on the blockchain and exploit that power to their advantage.

Maximal Extractable Value vs. Miner-Extractable Value

MEV is increasingly referred to as maximal extractable value instead of the original term miner extractable value. This is due to MEV not being limited to just miners in proof-of-work (PoW) blockchains, but also applying to validators in proof-of-stake (PoS) and other types of networks as well. To encompass the full scope of MEV across the multi-chain ecosystem, we’ll refer to the former terminology in this blog post.

MEV History

In the 2019 research paper entitled “Flash Boys 2.0,” the authors of which include Chainlink Labs researchers Ari Juels and Lorenz Breidenbach, MEV and transaction reordering are not just explained as a theoretical concept, but as a dynamic that is already occurring at scale in the form of transaction frontrunning on decentralized exchanges and which can have a significant impact on the user experience. By the start of 2021, the cumulative value of MEV extracted on Ethereum reached $78m, which then shot up to $554m by the end of the year. MEV extracted on Ethereum now stands at over $686m.

How Does MEV Work?

Blockchain networks such as Bitcoin and Ethereum are immutable ledgers secured by a decentralized network of computers, known as “block producers,” including miners in PoW blockchains and validators in PoS networks. These block producers are responsible for regularly aggregating pending transactions into blocks, which are then validated by the entire network and appended to the global ledger. While blockchain networks ensure all transactions are valid (e.g. no double-spends) and new blocks of transactions are continually produced (preventing downtime), there isn’t actually a guarantee that transactions will be ordered in the exact manner they were submitted to the blockchain.

Since each block can only contain a limited number of transactions, block producers have full autonomy in selecting which pending transactions in the mempool—the location block producers store unconfirmed transactions off-chain—they will include in their block. While block producers by default order transactions by the highest gas price (transaction fee) in order to maximize their profits, this is not a requirement by the network. As a result, block producers can extract additional value by taking advantage of their ability to arbitrarily reorder transactions, creating what is known as maximal-extractable value (MEV).

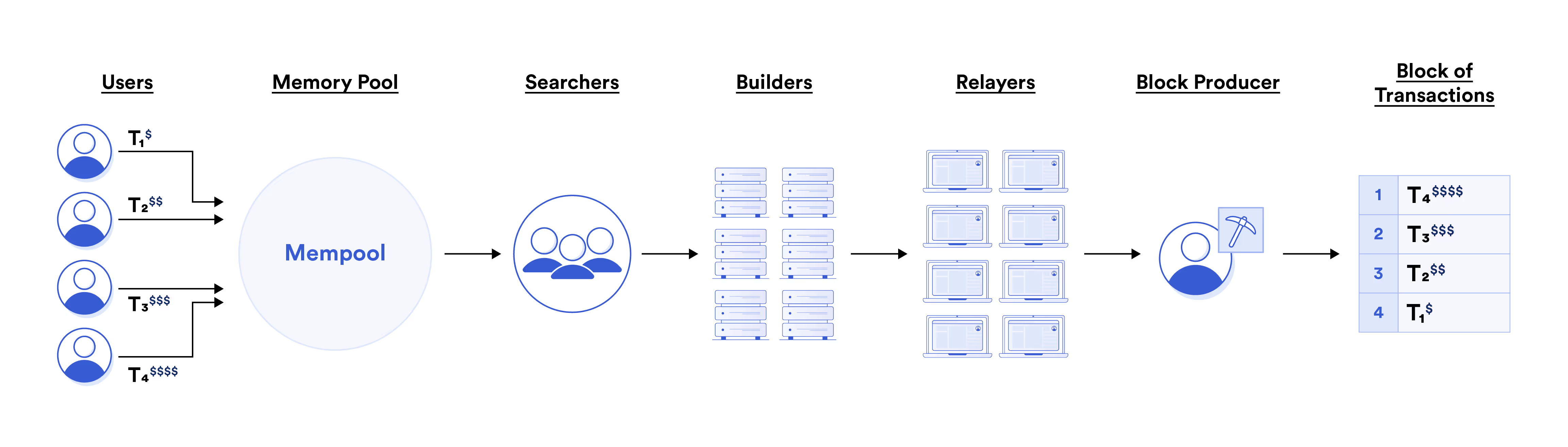

Due to the resources and expertise required to extract MEV, it is common for block producers in blockchain networks to outsource the creation of blocks to third-party networks consisting of searchers, builders, and relayers. Searchers seek out MEV opportunities and create bundles of multiple transactions, often containing another user’s transaction. These bundles are sent to a builder who combines the bundles into a full block payload. Builders then make available full blocks to relayers, which serve as the connection point to a blockchain’s block producers. Note that this is just one example of how block producers today extract MEV, but the ecosystem continues to rapidly evolve.

MEV often comes at the expense of regular users, many times in ways that may not be immediately apparent to all users until after their transaction is processed. This can include worse price execution for user trades, where MEV is directly extracted from users.

MEV Examples

While a definitive list of MEV extraction techniques would be challenging to collect due to the ongoing nature of the phenomenon and the financial incentive for searchers to keep their strategies obscured, there are a few well-documented examples of MEV.

Frontrunning and Sandwich Attacks

MEV that can be considered directly detrimental to the user experience is bots who frontrun trades made by users on decentralized exchanges (DEXs). Because transactions from users often go through a public mempool (a queue where unconfirmed blockchain transactions are stored), frontrunning bots can monitor for large trades and use this knowledge to their benefit.

For example, if a large trade is spotted, a frontrunning bot can copy the user’s trade and create a transaction bundle where their transaction is processed first before the user’s trade. This moves the market price of the asset being traded, causing the user’s trade to incur a larger amount of slippage—the difference between the expected price of a trade and the actual price. After the user’s trade is processed, the market price of the asset being traded further shifts in the frontrunner’s favor, which allows them to take profits by selling their assets via a backrun trade, resulting in what is commonly known as a “sandwich attack.”

As a result, the user’s trade is executed at a suboptimal exchange rate, increasing the costs of using decentralized exchanges in the form of an “invisible fee” where fewer tokens than initially expected are received.

Exchange Arbitrage and Liquidations

MEV can also take place when third-party bots perform arbitrage between two or more decentralized exchanges. An arbitrage opportunity is created when the price of a crypto asset on one exchange deviates from another, typically caused by a large trade on one of the exchanges. Arbitrage bots profit from this opportunity by purchasing an asset on the exchange offering a lower price and selling it on the exchange offering a higher price, bringing both exchange prices back to equilibrium while earning a profit. Additionally, arbitrage can also be performed between on-chain DEXs and off-chain centralized exchanges or between on-chain DEXs on two different blockchain networks (cross-domain MEV).

With the increased adoption of DeFi and growing liquidity within DEXs over time, the occurrence and profitability of these arbitrage opportunities have increased, leading to growing competition between arbitrage bots. These bots compete by engaging in bidding wars, which leads to them continually raising the fee they are willing to pay block producers in an attempt to get their bundles included in a produced block

While arbitrage is a normal healthy market activity, MEV bots can steal arbitrage opportunities from other users by monitoring the transaction mempool and copying the trades, while paying a higher fee to block producers for their transactions to be included rather than the original arbitrage transaction. A similar dynamic also takes place with the liquidation of collateralized loans in DeFi lending markets.

Generalized Frontrunning

A more advanced technique for the extraction of MEV are bots that engage in what is called generalized frontrunning. This involves a searcher scanning transactions in a public mempool and submitting an identical transaction with a higher fee to block producers, while replacing any occurrence of the user’s address in the transaction payload with their own. This has already been seen in practice where a white-hat hack to rescue at-risk user funds was thwarted by a generalized frontrunner copying/replacing a crucial transaction with their own. Such bots usually don’t interpret what the transaction is doing, but rather simply run an algorithm to scan mempool transactions, replace addresses in the transaction’s payload, and simulate its execution to detect if it results in profit.

These are just a few examples of how MEV is extracted and how it can adversely affect users. However, they are not the only situations in which MEV is possible. If and when block producers begin to capture more MEV opportunities for themselves, it is possible that more advanced reordering strategies are used to further extract value from users.

MEV Pros and Cons

While MEV is generally considered a negative by most developers and users across the industry, there are some benefits.

Pros

MEV plays a role in helping mitigate economic inefficiencies across DeFi protocols. For example, rapid liquidations enabled by MEV help ensure that lenders get paid back when borrowers fall below the specified collateralization ratio. Also, arbitrage traders can help ensure that token prices on various DEXs more closely reflect market-wide demand. As economically rational actors leverage MEV to maximize their profits, this can help minimize the economic inefficiencies of individual protocols, ultimately helping make the DeFi ecosystem more efficient and robust.

Proponents also argue that MEV increases a blockchain network’s security by incentivizing miners or validators to compete for the opportunity to produce blocks.

Cons

MEV can create a worse experience for end-users, such as when a DEX sandwich attack creates high slippage during a trade execution. Also, as generalized frontrunners are willing to pay more gas fees to ensure their transactions are factored into the next price, the network can become congested, which raises the price for all transactions on the network. Moreover, if the MEV available to block producers exceeds the block reward, they may be incentivized to reorg previous blocks in order to capture MEV, which can lead to consensus instability.

Mitigating MEV: Chainlink Fair Sequencing Services (FSS)

In order to mitigate the detrimental effects of MEV, Chainlink is developing Fair Sequencing Services (FSS)—a transaction ordering solution using decentralized oracle networks. Chainlink FSS works by collecting user transactions off-chain, generating decentralized consensus for transaction ordering, and submitting the ordered transactions on-chain, in a decentralized way.

As explored by Chainlink Labs’ Chief Scientist Ari Juels in a recent presentation at SmartCon 2022, FSS is being designed to help increase order fairness, reduce transaction costs, and reduce or eliminate information leaks.

The first component of this design involves secure causal ordering (atomic broadcast), where user transactions are first encrypted by users to hide transaction details, ordered by a decentralized oracle network, and then decrypted for execution on a blockchain network. As a result, the transaction payload will not be visible to nodes before the ordering process begins, removing the ability to front-run transactions based on early visibility.

The second component, temporal ordering, is a mechanism aiming to ensure that the transactions received first by the oracle network are the first to be output, helping ensure a first-in, first-out (FIFO) ordering policy.

When combined with transaction encryption, a defense-in-depth solution is enabled for the fair ordering of user transactions. The technology making FSS possible is further explored in-depth within section 5 of the Chainlink 2.0 whitepaper.

Fundamentally, Chainlink FSS aims to decentralize the process of transaction ordering, helping ensure that smart contracts process transactions in a provably fair manner devoid of any preferential ordering. Chainlink FSS can be used in various ways, including serving as a pre-processing stage for smart contracts on a layer-1 blockchain, as well as ordering transactions for layer-2 networks and decentralizing rollup sequencers.

By helping ensure transactions are ordered fairly and lowering network transaction fees, FSS drastically improves the user experience of interacting with smart contract applications. The end result is a DeFi ecosystem that is able to achieve its highest potential of providing a more economically fair world, backed by distributed consensus and cryptographically enforced guarantees.

If you’re a developer and want to connect your smart contract to existing data and infrastructure outside the underlying blockchain, visit the Chainlink developer documentation or reach out here.